Search for Family Identity

It is only since about 1977 that there has been a clear understanding of the American Christlieb’s family origins. Benjamin Franklin Christlieb’s writings reveal that the Pennsylvania branch of the family carried a tradition that their immigrant ancestor had been in some way connected with a ruling family in Germany; however, they did not fully understand what that connection had been.

While writing The Christlieb Family, B.F. Christlieb had in his possession a copy of Friedrich Carl II’s baptismal record (since lost) that had been procured from the office of the Leiningen-Hartenburg Consistory on May 1, 1765. In those days, a baptismal record served as a passport, legally permitting its owner to travel from one principality in Germany to another or to leave the country.

After reading a translation of the old document, B.F. Christlieb was curious about the presence of the Count and Countess of Leiningen-Dagsburg-Hartenburg and family at his grandfather’s baptism. The information in the baptismal document reinforced the family’s oral tradition that the Christliebs had somehow been connected with a ruling family in Germany, and it intensified B.F. Christlieb’s desire to delve deeper into the family history.

Around 1875, Benjamin Franklin Christlieb contacted the United States Consul at Mannheim, Germany, who in turn put him in touch with A. Frey, Recorder at Dürkheim, who searched the Dürkheim church records for further information. The following is a paraphrased version of Frey’s investigation:

“…after an examination of the records, in which the original of the foregoing certificate of baptism still exists, from 1743 to 1765, no other item besides the original of the foregoing certificate pertaining to the family was found, and the fact of the birth and baptism of the elder and only brother of the subject of baptism [Jacob], who was also born in Germany within the period examined, not appearing in the same records, would indicate that the family had resided at other places in Germany and locating at or in the vicinity of Dürkheim a short time previous to the birth of the younger son, the subject of baptism in the foregoing certificate.” The Christlieb Family, p. 6.

Before going further, it must be pointed out that the church records for 18th-century Dürkheim, are to be found in two large leather-bound volumes. The first of these contains baptismal, marriage, and death records from the early years of the century through 1750; the second volume’s entries date from 1751 to 1798.

In his search for Jacob’s baptismal entry, Herr Frey would have checked out the first volume, as B.F. Christlieb had instructed him to search for Jacob’s baptismal entry, which he incorrectly believed to have been in 1747.

After not finding Jacob’s baptismal entry at the end of the earlier register, Frey would probably have given the book a thorough going over. In so doing, he would have discovered Friedrich Carl’s baptismal and marriage entries, both of which occurred in 1742. By stating that nothing further on the family could be found from 1743 to 1765, he stayed close to the truth without revealing the truth. The baptismal and marriage entries plainly acknowledged Friedrich Carl’s Jewish origins.

Back to TopThe Turkish Child

Benjamin Franklin Christlieb’s writings reveal that he became acquainted with Professor Theodor Christlieb, D.D., Ph.D., of the University of Bonn, when the acclaimed theologian was on a lecture tour of the United States in 1873. From him, B.F. Christlieb learned that Theodor Christlieb was a descendant of a Turkish boy who had been found in an outdoor oven, where his mother had hid him during the Battle of Belgrade. When the slaughter was over, the child was found alive by Prince Eugene and taken back to Germany, where he was reared at the Court of Baden Durlach. When grown, the Turkish orphan became an artist of the Court. Tradition within Theodor Christlieb’s family taught that the child was given the surname, Christlieb, because it was through Christ’s love that his life had been spared.

Aware that his great-grandfather had been associated with a ruling family in Germany, B.F. Christlieb entertained the idea that Friedrich Carl Christlieb and the Christlieb who was reared at Baden-Durlach may have been one-and-the-same person. He concluded his history of the family with the following:

“There seems to be, however, some plausibility to the suggestions of Prof. Christlieb that the American family descended from, and had its origin while the Turkish boy was still in Baden. The infrequency of the name, the fact of both traditions pointing to a similar circumstance, an association with a European Court, and proximity of the localities mentioned in both traditions—the cities of Baden, Stuttgart, Durlach, Mannheim and Dürkheim being situated at no great distance from each other—one hundred English miles being the greatest distance between any two of those places, gives weight to the supposition that the two families originated from the same ancestor.” The Christlieb Family, pp. 51, 52.

Although Benjamin Franklin Christlieb never said with certainty that the American family descended from the Turkish boy, the story nevertheless made its way into the family tradition, where it was accepted as fact until disproven in 1976.

Returning to the aforementioned report from the Dürkheim Recorder, one does wonder if Benjamin Franklin Christlieb may have edited Herr Frey’s statement. Regarding which of the two men was responsible for suppressing Friedrich Carl’s Jewish origins, two possible scenarios come to mind:

1. In his letter to the Dürkheim recorder, Benjamin Franklin Christlieb enthusiastically wrote of his belief that he was quite possibly a descendant of the Turkish boy who had been reared at the Court of Baden-Durlach. After noting Friedrich Carl’s Jewish background in both the baptismal and marriage entries, Frey avoided telling him of it by stating that he found no further information from 1743 to 1765. In writing a truthful but not completely honest report, he spared B.F. Christlieb the disappointment of not being a descendant of the Baden-Durlach Christlieb, and he avoided telling B.F. Christlieb that his German ancestor was a Jew by birth.

2. Another possibility is that the Dürkheim recorder conveyed his findings to B.F. Christlieb, who upon learning that his great-grandfather had been a Jew, had to decide whether to include the information in his history or suppress it. Taking into consideration the prevailing attitudes towards Jews at the time, B.F. Christlieb chose to ignore the information. It is the opinion of the author that the second scenario is the more plausible of the two. By his own admission, B.F. Christlieb had suppressed other information that he perceived to be negative in nature.

When Friedrich Carl became a Christian, he created a new life for himself. Being a member of the Christian community would have required that he disassociate himself from his Jewish family and they from him. Although proud of his link with the Houses of Leiningen, Friedrich Carl appears to have been vague in revealing details of the one-time connection, for to have done so would have meant revealing that he had been born a Jew.

One reminder of Friedrich Carl’s former life that remained with him for the rest of his life would have been his circumcision. It is doubtful that, in the days when fathers and sons bathed together in rivers and streams, Friedrich Carl could have kept his circumcision hidden from his sons. If Jacob or Carl knew of their father’s Jewish heritage, they did not pass it on to their own children. If they had, Isaac Christlieb, son of Carl and the family’s first historian, would have passed the information on to his son, Benjamin Franklin Christlieb.

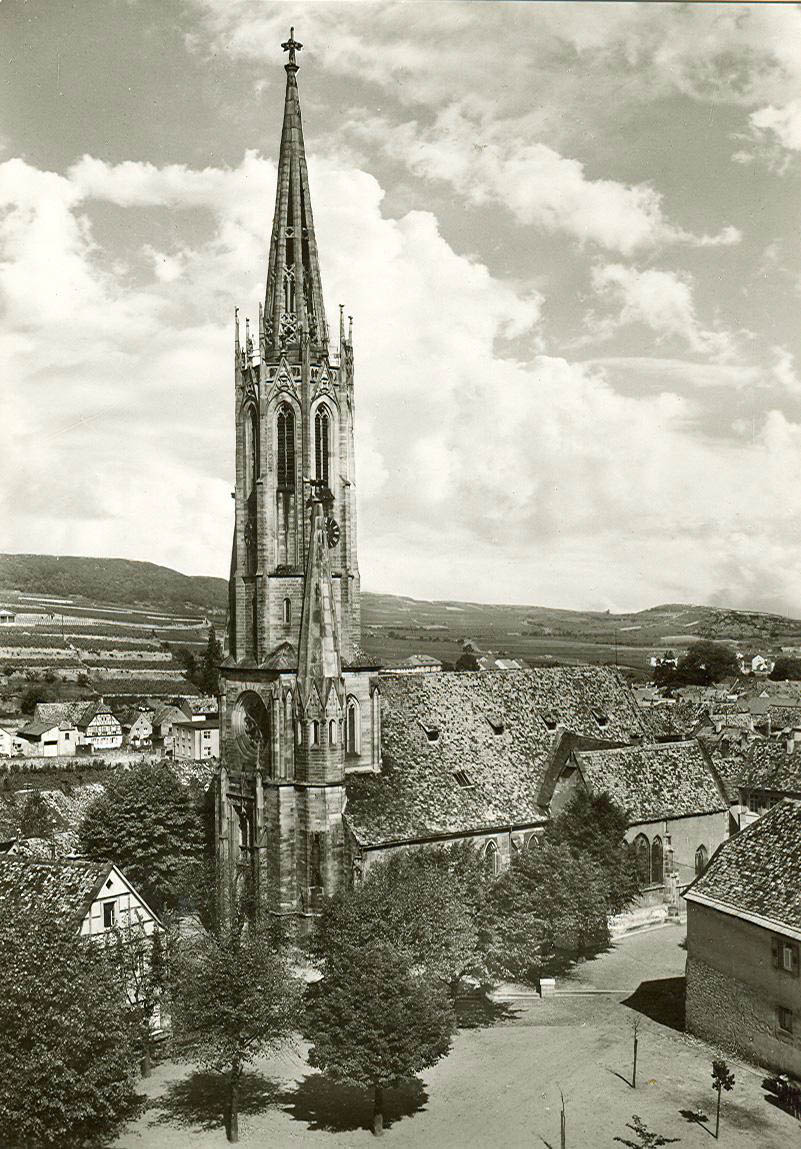

Shown here with its magnificent nineteenth-century Gothic tower is the ancestral church of the American Christlieb family, the site of Friedrich Carl Christlieb's adult baptism. Dating from 946 A.D., and named in honor of St. John the Baptist, Catholics worshipped here until the Protestant Reformation. Later, when the Counts of Leiningen built their new palace at Dürkheim, the Church became known as the Castle Church [Schlosskirche]. Through marriage, baptisms, confirmations, and death, the American Christlieb Family's origins are forever embedded in this place.